Distilling reality: documenting the Renaissance in Florence

What Nike, bronze doors and orphanages have to do with metadata.

What Nike, bronze doors and orphanages have to do with metadata.

In 2011, David Battistella, a Canadian-born DP, relocated back to his parents’ hometown Firenze. Renowned for its Renaissance beauty, David’s roots led him to document the local history. But, instead of showing off the visual splendor and grandeur of Florence’s monumental architecture and art, he has gone down to the base of it all: daily life. The blood, sweat, and tears that have been put into construction, and nowadays into restoration. The grunt work. It has made him think about metadata on a whole different level. Metadata first, you could call it.

Medieval metadata

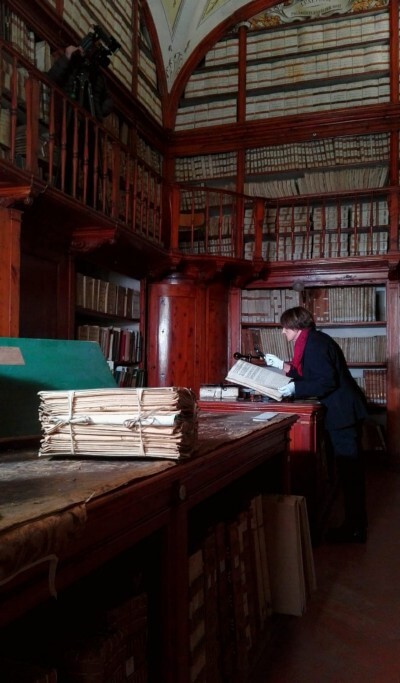

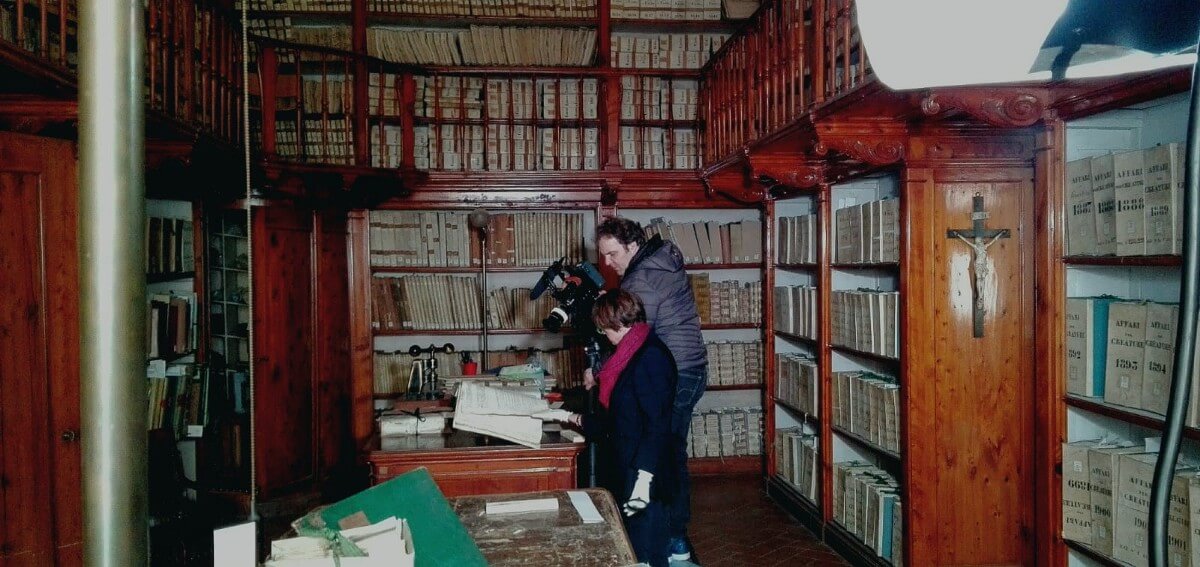

“When combing through archives, researching history, especially the kind of history that goes back 600 years or something, we’re mostly just left with documents. I have found myself thinking over and over again “How I wish there were a camera or microphone, that somebody recorded something.” The documentation has become extremely important — without it’s as if something doesn’t exist. It’s a fascinating realization. The metadata and the surrounding documentation around a shot I capture today will probably become more important than the image itself. ”

David’s current undertaking is a documentary about the restoration of the famous Cupola.

“Preservation of metadata is the only reason that we know so much about the history of Firenze’s Cupola. One woman spent 16 years on deciphering and translating the documents about its construction. It took that long because the building itself also took 16 years. Over that span of time, there were different scribes, each with a different hand. They also used different languages like Latin and vulgare — the Italian of that particular time. But the key here is that they’re financial records. What that means is that you know what they spent money on. It’s like what advertisers do nowadays, by tracking you: what is David doing with his phone, what did he buy, where did he lunch, when did he go online at this time in the evening. It’s proof.

Someone in the team had this theory that the entire Cupola is reinforced with iron. That means someone must have bought iron for it, and if there’s no record of that, it must have been donated. Such a significant donation demanded a building or a plaque, and since that doesn’t exist it most probably just didn’t happen. That’s a powerful way of leveraging financial records, before jumping to conclusions and tearing down a wall. It actually leads us to valuable insight if hunted down — not just now, but a hundred years from now, when another restoration might be going on.”

Behind the eye

“When I used to take photographs with film, I’d have this contact sheet and circle the four shots that were great. If you ever go back to that roll of 36 with all the rejects, you might realize there are absolute gems in those 32 once useless shots. Back then you weren’t paying attention because you were in a different line of inquiry at the time. So the metadata is critical. It tells you so much more. At a glance, you’d find that one shot you knew you made that shoot. Nowadays, it’s the same with R3Ds: often the metadata itself might tell you more about the image than your eyes can tell you by looking at something.

Because we’re documenting, the simplest thing to do is to at least make sure the camera has the right date and time set. So effortless, it makes all the difference later on. What day did I start making this film? When was the first shoot? That’s something you gain from caring about metadata. But to make it really useful, we should crowdsource it. To look at it as big data.”

Big data

“We’re not in any way taking the full advantage of metadata to create big data, today. Everybody’s talking about it, everybody wants to do it, but it’s tough to convince people that it’s essential in the daily routine. What if somebody a hundred years from now looks at it, and thinks “this is just a shot of some wooden panel?” Other threads of info could be pulled together for a much better understanding turning it into something more significant than a silly project about how a restoration took place.

Among some of the work I’m doing, is the restoration of bronze doors of the Baptistry. They’re dated around 1246, made by Andrea Pizano, and currently in the restoration lab. They’re cleaning them, and I’m documenting that process. The type of mercury they’re using to fuse the gold leaf to the doors is an outlawed process nowadays. It’s too dangerous, even lethal. There’s only one place left where it can be done, in France. Whatever they’ve learned could inform someone across the world who finds a similar object with the same technique. Without big data, others simply will not know. It’s hard to get people into that mindset, to think beyond their own project and needs.

I use a slate to tell people what a scene is about, so that’s a visual representation, but what I’d really want to do is put that footage into an online pool to create a database where the people working on this can add their notes. For narrative, LightIron nailed this. But factual is another world. The visual researchers and the conservator look completely different at my footage than I might be — since I try to make a beautiful image, but they’re looking at what a particular speck of gold looks like when reflecting a laser. That’s the power of those 32 rejected photographs, so to speak. My B-roll might be the most crucial piece of information to the person next to me. They see things in it I do not see. Each person sees the footage from their own perspective.”

Studying artisans

“I wonder why these 15th-century people were so productive? We have all the technology, yet the artists of the Renaissance were so prolific, it seems. They produced so much work. It led me to this idea of the importance of just chipping away at your work on a daily basis, not just thinking about it in the long term — “I need to make this big film” or “I need to work out the complete film before shooting even a single frame.”

So I started examining daily work. I just got delivery of my RED EPIC, and wanting to honor the analog process of film with this digital beast, I made a film about a photographer using 8x10 sheets, a 1 frame camera, and doing processing in a dark room. I wanted to use the new tool to honor craftsmanship. Someone that has all that knowledge to make one, maybe two frames is pretty rare in the Instagram age where you might try that same shot 20 times.”

Swooshes and paintings

The Innocents Of Florence is a documentary about the restoration of one painting: The Mother of the Innocents. It was commissioned by the institute in 1446. Its intended use is as a banner painting to be carries in processions to represent the institute. Next to that, it was used as an altar piece in the church inside the institute. It now resides in the Innocenti museum in Piazza S. Annunziata in Florence.

“There’s something about how these art conservators work. What is their process when taking a 600-year-old painting into their studio? How responsible must these people feel? How do you even start to touch that canvas with anything at all, where does the knowledge come from? It’s fascinating to me.

I began to understand why the painter even painted this painting in the first place. What value does it have that we want to care for it so delicately to bring it back to its current state? People might think conservation is a big waste of time, but it’s an exciting journey about preserving our past — it might look nostalgic, but it does tell us things. With this painting, I found out there it represented a whole institute, an orphanage of a sort that was unique at that time in the world. That’s why the painting exists.

For people to understand that in modern terms, I like to compare it to explaining Nike to someone, but only using its logo, the Swoosh:

The Swoosh is depicted on a running shoe, but it’s made by a guy who used waffle irons to make rubber things trying to create the best running shoe, turned it into a brand, and at some point all athletes used it.

There’s a lot behind what’s “just” a Swoosh if that’s your only representation, the only remnant of a particular part of history. This painting is a Swoosh.

It’s a painting that represents positively using wealth to save lives of children in an era. That activity grew into the Academia, the art academy of Firenze where so many artists came out of, and a center where the earliest form of gynecology research started.”

Essence

“You move from documenting into storytelling — although I don’t like to call myself a storyteller. I’m more a reteller since the stories already happened. I love the reality compression chamber metaphor for an edit room. You need to distill all you have into the essence. It is the reality to the viewers, but at the same moment, there’s so much more that is also real. I met a priest that worked in the Duomo in the same job for 50 years. 50 years of the same spiritual work, can you imagine that? Many of the people that worked on the Cupola knew and still know they’d never see it finished.

Could you imagine telling a young person today that they would start on a job to build or create something and they would never have the satisfaction of seeing it created? Maybe their great grandchildren would, but they themselves would work on it an entire lifetime and never see the work finished. That is a mindset of patience and faith and that is what a city like this one was built on.

The concept that you don’t know how it will end up and it’s not up to you either, but staying on that path will get it finished one day — how does that distill in a lifetime?”